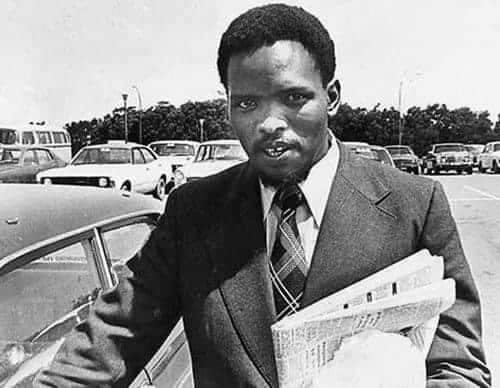

Black Consciousness was brutally murdered in police custody by the apartheid regime on September 12, 1977. (Photo: Supplied)

Forty-eight years ago, on 12 September 1977, South Africa lost one of its most uncompromising voices for black liberation. Stephen Bantu Biko, the charismatic leader of the Black Consciousness Movement, died in police custody at just 30 years old. His body bore the marks of brutality, his voice was silenced, but his ideas—about self-reliance, dignity, and the power of the black mind—continue to echo through South Africa and beyond.

Today, as the country commemorates his death, the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) has announced the reopening of the inquest into his killing. For the Biko family, the decision reopens old wounds, but it also offers a glimmer of justice long denied. For South Africa, it is a reminder of both the unfinished business of the past and the urgent questions of the present.

Biko’s family, who buried him in King William’s Town (Qonce) on 25 September 1977, have carried the burden of grief for decades. They have witnessed the first inquest in 1977 that exonerated his killers, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) hearings of 1997 where apartheid officers admitted to lying but escaped accountability, and now, in 2025, yet another chapter.

For them, the reopening is bittersweet. On one hand, it acknowledges the state’s failures in delivering justice in 1977. On the other, it forces them to relive the horror of a husband, father, and brother who never came home.

Biko’s widow, Dr Ntsiki Biko, has often spoken about how the family lives with an unhealed wound. In an earlier interview, she said: “We have never had closure. For us, Steve’s death was not only the loss of a loved one, it was the theft of a future. We raised children in the shadow of his absence. Justice is not about revenge—it is about truth.”

His eldest son, Nkosinathi Biko, echoed this sentiment. In response to previous legal processes, he once said: “It has always been important to our family that the truth of what happened to my father is acknowledged in a court of law. The lies that were told for so long cannot stand as the historical record.”

Their words underline that the inquest is not simply a legal matter. It is a fight for dignity, memory, and truth.

Biko’s is not the first apartheid-era death in detention to be revisited. In recent years, several high-profile cases have been reopened. In 2017, the inquest into the 1971 death of anti-apartheid activist Ahmed Timol concluded that he had been murdered by police, overturning decades of lies that he had jumped to his death. Similarly, the inquest into the 1969 death of Dr Neil Aggett found in 2020 that he had been tortured, and that police bore responsibility.

These cases point to a broader shift: the recognition that the truth buried by the apartheid security state must be exhumed. Yet they also highlight the slow pace of justice. Many of the perpetrators are now dead, and others are elderly. For families like the Bikos, justice delayed often feels like justice denied.

On X (formerly Twitter), Dr Mbuyiseni Ndlozi offered a searing tribute. He described Biko as “a proud black man, with an independent mind,” quoting the activist’s famous words: “The most potent weapon in the hands of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed.”

Ndlozi’s reflection went beyond nostalgia. He asked piercing questions about the state of South Africa and the African continent: How can Africa, so rich in resources, remain poor, diseased, and underdeveloped? Why do African leaders continue to look to the West for solutions, instead of finding answers within their own soil and minds? How can leaders who come from impoverished communities steal from those same communities, leaving them without water, electricity, or dignity? Why do some political leaders collaborate with criminal syndicates, loot the state, and silence whistleblowers?

His critique was not merely rhetorical. It was a challenge to South Africans to consider whether they have truly liberated their minds—or whether, as he put it, “we conduct ourselves in the internet of the oppressors’ superiority.”

Would Biko Be Proud of South Africa Today?

It is tempting, on commemorative days, to simply celebrate Biko’s life. But the harder task is to confront whether his vision has been realised. Would Biko be proud of South Africa in 2025?

He would likely marvel at the fact that South Africa is a constitutional democracy, where freedom of expression and the right to vote are protected. He would see his words etched into school textbooks, his ideas commemorated in public holidays and university courses.

But he would also see staggering inequality, with black poverty and unemployment entrenched nearly three decades after democracy. He would witness service delivery protests in townships where children still learn under trees and fetch water from rivers. He would hear of corruption scandals that hollow out public trust and squander the resources of the people. He would see political leaders living in opulence while shack settlements expand.

Biko might ask, as Ndlozi did, “Where is our mind?” He would likely argue that political freedom has not yet translated into true psychological liberation or economic justice. He might lament that too many South Africans still measure progress by the approval of the West, rather than by the standards of African dignity and self-determination.

The Call for Justice

The reopening of Biko’s inquest, therefore, is not just about one man’s death. It is about whether South Africa can confront its past honestly, hold perpetrators accountable, and restore dignity to the families who sacrificed everything for freedom. It is about whether the law can finally stand where it faltered in 1977, when the magistrate rubber-stamped lies and shielded killers.

The Forum for South Africa (FOSA), welcoming the inquest, noted that the process is “an opportunity to provide closure to the Biko family and to the nation.” Closure may be elusive, but truth and accountability are indispensable steps.

The Mind as a Battlefield

Biko once wrote, “I’m going to be me as I am, and you can beat me or jail me or even kill me, but I’m not going to be what you want me to be.” His insistence on intellectual and psychological freedom remains a radical call.

As the inquest reopens in Gqeberha High Court, the real question is not just whether the court will find anyone responsible for Biko’s death. It is whether South Africans will reclaim the dignity of their minds from the corruption, apathy, and inequality that threaten to betray the sacrifices of heroes like Biko.

On this 12th of September, the nation remembers not only a martyr but a mirror. Steve Biko died at 30, but his ideas remain ageless. They invite every generation to ask: Where is our mind, and what will we do with it?