The first sitting of South Africa’s much-anticipated National Convention — a gathering billed as the start of a “million conversations” to confront the country’s social and economic crises — began in Pretoria on Friday under a cloud of tension.

Earlier in the day, chaos briefly erupted inside the venue at UNISA’s main campus, where senior officials were seen in a heated argument near the delegates’ entrance. Witnesses described raised voices, flurries of pointing fingers, and security personnel stepping in to defuse the situation.

Outside the gates, protesters from various civic movements, including unemployed youth groups and labour unions, held placards demanding urgent action on job creation, service delivery, and corruption. “We are tired of talk shops — we need action, not more speeches,” read one sign. Another declared, “National Dialogue must mean change for the poor.”

Among the notable attendees inside the hall was Joseph Mathunjwa, president of the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (AMCU) and a key figure in the 2012 Marikana strike — a labour dispute that ended with police killing 34 mineworkers. Mathunjwa’s presence was symbolic for many, evoking the unresolved grievances of Marikana widows, injured miners, and communities still battling poverty and unemployment more than a decade later. He told journalists ahead of the session that “any dialogue about South Africa’s future must be honest about the deep inequality and injustice that still defines our economy.”

Opening the convention, President Cyril Ramaphosa invoked Section 83 of the Constitution, saying his duty as head of state was to “promote the unity of the nation and advance the Republic.”

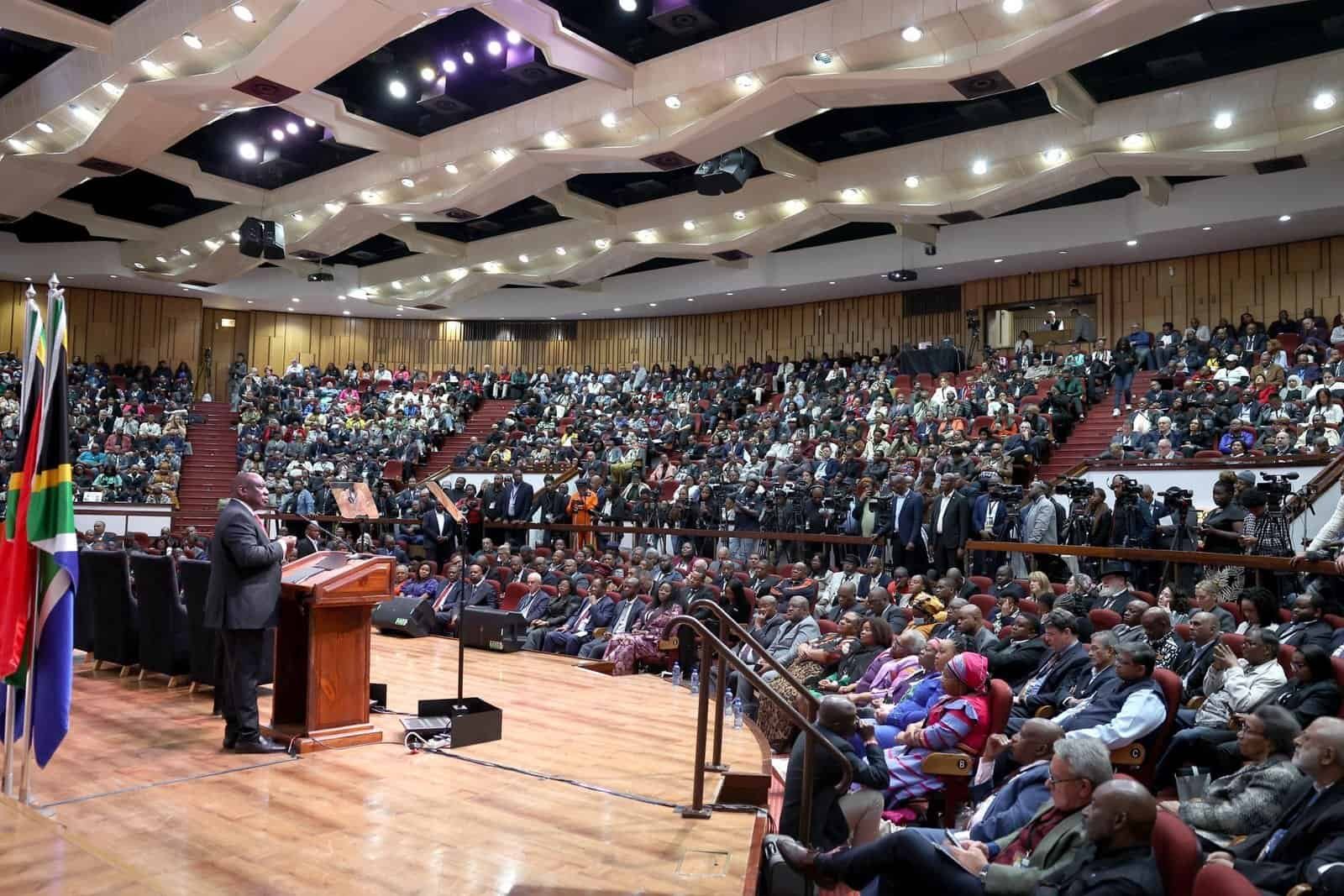

“This is not a partisan platform. This is a national platform,” Ramaphosa told the packed hall of over 1,000 delegates representing more than 200 organisations from across the country. “No voice is too small, and no perspective is too inconvenient to be heard.”

The President painted a frank picture of South Africa’s challenges — economic hardship, mass unemployment, entrenched inequality, growing poverty, and a crisis of confidence in institutions — but said the country’s history showed it could respond to adversity with unity.

“We gather here today in all our diversity to launch a National Dialogue,” he said. “This process will take us to every corner of our country — from informal settlements to rural villages, from churches to classrooms, from online platforms to radio call-ins. We will have difficult conversations about poverty, gender-based violence, discrimination, and why the prospects for a white child are still so much better than those of a black child.”

The convention brought together a strikingly varied mix — from farmers and informal traders to artists, sports stars, and community activists. High-profile members of the Eminent Persons Group — including Archbishop Thabo Makgoba, Dr Imtiaz Sooliman, Springbok captain Siya Kolisi, and Miss South Africa 2024 Mia le Roux — sat alongside traditional leaders and former political heavyweights.

For many, the presence of grassroots representatives like waste pickers, unemployed graduates, and survivors of violence was just as important. “If we only listen to the elite, we will fail,” said Thandiwe Molefe, a delegate from a women’s cooperative in the Eastern Cape. “We need to hear the voices of the township and the rural village.”

While Ramaphosa urged optimism, the protests outside revealed the depth of public scepticism. Some demonstrators accused the government of using the convention as a distraction from corruption scandals and service-delivery failures.

One group of unemployed graduates, wearing academic gowns, chanted “Education without jobs is useless!” Another cluster of placard-wielding activists demanded justice for victims of state violence, holding portraits of Marikana mineworkers.

“This dialogue is long overdue, but we’ll judge it by outcomes,” said Mxolisi Dlamini, a youth activist from KwaZulu-Natal. “We don’t want this to be another Polokwane or Codesa moment that leaves ordinary people behind.”

The inclusion of Marikana’s leadership in the convention underscored the still-raw wound of the 2012 tragedy. Despite a lengthy commission of inquiry, survivors and families of the slain miners say they have yet to receive full compensation or see any police officers prosecuted.

Mathunjwa told journalists that the National Dialogue must address systemic economic injustices, especially in the mining sector. “Marikana was not an accident; it was the product of a system that puts profits above people,” he said. “If we cannot talk honestly about that, then we cannot talk about a just South Africa.”

Said Ramaphosa emphasised that the dialogue was a call to action. “These are challenges we must be ready to do something about — as individuals, as organisations, as communities, as public officials,” he said.

He called for a “shared national vision” that would lead to political stability, economic renewal, social cohesion, and a capable, ethical state. The process, he said, must result in a social compact that clearly defines the responsibilities of citizens, government, business, labour, and civil society.

“This Convention should not be remembered for fine speeches alone,” Ramaphosa warned, “but for the process it begins towards a new roadmap for South Africa.”

Over the next six to eight months, thousands of public dialogues are expected to take place across the country. Delegates at the convention will serve as “champions” of these discussions, tasked with ensuring inclusivity and fostering an environment for constructive debate.

Whether the National Dialogue can overcome scepticism and deliver tangible change remains to be seen. But for one day in Pretoria, under the watchful eyes of protesters and amid echoes of Marikana, South Africa’s leaders, activists, and citizens sat down to talk — and perhaps, to listen.