It is necessary to clarify from the outset: this opinion piece is not written by a political scientist but by a decolonial, Africana scholar. My interest lies not in the mere mechanics of “governance” or the liberal tropes of “good administration,” but in the more profound, more haunting questions of power, continuity, and the persistent coloniality that governs the South African state.

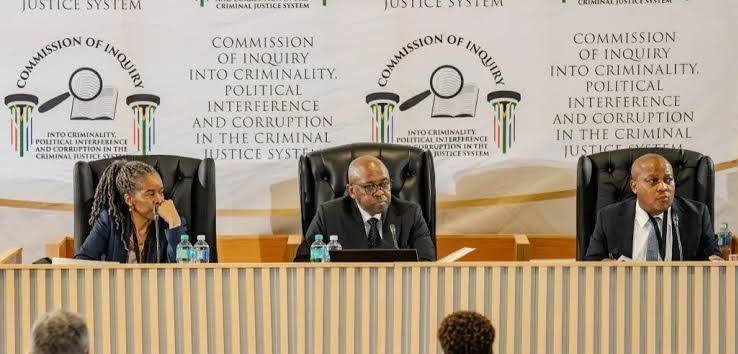

For too long, the South African public has been fed a sanitised account of our transition; a narrative of a miraculous “rainbow” birth that supposedly severed our ties to a dark past. However, as the Madlanga Commission (the Judicial Commission of Inquiry into Criminality, Political Interference, and Corruption in the Criminal Justice System) laid bare the systemic hollowing out of our justice apparatus in 2026, we are forced to confront a more terrifying reality. We are witnessing not new corruption, but the “Second Wave” of a criminal logic that was never dismantled.

To understand the testimony currently echoing through the halls of the Madlanga Commission, one must first engage with the forensic cartography presented by Hennie van Vuuren in Apartheid Guns and Money. Van Vuuren’s work is not merely a history of sanctions-busting; it is a decolonial text that exposes the “Deep State” as a globalised criminal syndicate. He demonstrates that the apartheid regime was sustained by a labyrinth of front companies, secret service funds, and offshore accounts, facilitated by European financial giants such as Kredietbank.

This was the “Arms Money Machine”, a structure that prioritised the survival of white supremacy and capital over any semblance of human rights. Van Vuuren’s thesis is essential to the Africana perspective: he shows that the apartheid state “walked through open doors” behind the scenes, sustained by international accomplices who treated African lives as collateral for profit.

The tragedy of our democracy is that the 1994 settlement focused on political optics while leaving the apartheid state’s economic and clandestine plumbing intact. Van Vuuren argues that because the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) failed to investigate economic crimes, focusing instead on individual human rights violations, the architects of the “Deep State” were allowed to transition into the new dispensation. They did not retire; they changed their rhetoric and “invited the new elite to the table”.

This brings us to the chilling revelations of the Madlanga Commission.

Justice Madlanga has uncovered the deliberate “neutralisation” of 121 active investigation dockets, many of which involve political assassinations in KwaZulu-Natal. These dockets were not lost in a bureaucratic muddle; they were systematically hijacked and moved to the highest levels of police command to ensure they remained dead.

As an Africana scholar, I see this not as “mismanagement” but as the “Coloniality of Capture.” The same methodology used by the apartheid securocrats to conceal the procurement of Puma helicopters and missile technology is now being used to shield a new class of political and criminal predators. The “malleable functionaries” Justice Madlanga identifies in the SAPS and the NPA are the direct ideological descendants of the “securocrats” documented by van Vuuren.

The most harrowing continuity, however, is the use of lethal violence to protect these secret networks. Van Vuuren’s research into the 1988 assassination of Dulcie September in Paris serves as a haunting prologue to the current state of affairs. September was murdered for threatening to expose the trade routes of the apartheid money machine. Decades later, in December 2025, Marius van der Merwe, a key witness before the MadlangaCommission, was brutally assassinated in front of his family.

These are not isolated crimes. They are “maintenance killings” designed to protect the “Long Shadow” of the criminal state. Whether it is the apartheid “Deep State” or the modern “Criminal Syndicate,” the logic remains the same: preserving the secret is worth more than a black life or the integrity of a witness. When the “right to know” threatens the “right to profit,” the state, or the shadow state within it, resorts to the ultimate silencing.

The Madlanga Commission is effectively conducting a forensic audit of a failed transition. It shows us that the “Guns and Money” have simply found new hands to hold them. By hollowing out the justice system, the capturing forces have ensured that the law remains a tool for the powerful and a trap for the marginalised.

From a decolonial perspective, we must stop treating “State Capture” as a contemporary African failure. Instead, it is a structural legacy of the secretive, unaccountable state machinery built to defend minority rule. The “sophisticated criminal syndicates” that Justice Madlanga is currently investigating are utilising the very same offshore infrastructures and “off-the-books” operations that van Vuuren uncovered in the archives of the 1970s.

The question we must ask, which neither a political scientist nor a lawyer can fully answer, is whether a state built on the foundation of criminal secrecy can ever truly be “reformed” through commissions?

If we rely solely on the “source truth” of Van Vuuren and Madlanga, the answer is sobering. Until we follow the money into the boardrooms and offshore accounts that survived 1994, and dismantle the culture of secrecy that allows 121 dockets to “vanish” at the stroke of a pen, our liberation remains a hallucination.

The Madlanga Commission is our last chance to perform the surgery the TRC shirked. We are not just fighting to “fix” the police; we are fighting to dismantle a centuries-old labyrinth of profit and blood. The shadow is long, but as the evidence mounts, the “open secrets” of our past and present are finally dragged into the unforgiving light of the African sun.

Mothoagae is a Professor in the Department of Gender and Sexuality Studies at the Unisa College of Human Sciences. He writes in his personal capacity.